How can 9/11 and blockchains be linked? By a discussion about self-sovereign identity at a blockchain convention, of course.

Self-sovereign identity is the concept that people, themselves, can be responsible for storing data about their identities, and have the ability to give that data to other parties in a credibly attested way.

Wot??

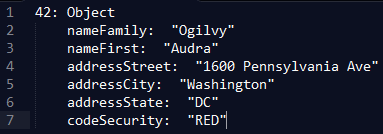

The current norm is to give our data away to any party we want to interact with who asks us for that data. How many times have you keyed your address into an online form? Right now big data is a hot topic in the tech world. So is machine learning. And as databases become engineered by machine learning, imagine how many bits of identity data will be accessible to government.

I wouldn’t have thought this subject would interest me because I’ve steered clear from topics that smell conspiracy-theory-ish. I’ve always had other things that concerned me more. Things like wondering where I was going to find a roof over my head when I was a teenager outweighed worries about the government hording bits of data. And while I do believe in a person’s right to privacy, I, myself, live an “open book” life. I unwittingly adapted a straight-up, WYSIWYG personality, because life is busy and complicated as it is, so I like to simplify things that can be simplified, and that means having nothing to hide from the government. So when people started complaining about things like Facebook storing information about its users, I stuck up for Facebook. (I still do.) It’s a free service, and I always assumed that anything I put on there could be used for marketing (duh) or some other purpose. And who cares?

storing information about its users, I stuck up for Facebook. (I still do.) It’s a free service, and I always assumed that anything I put on there could be used for marketing (duh) or some other purpose. And who cares?

And this is why I loved the talk between Andreas Antonopoulos, John Cutler, Amber Scott, and Ana Badour. I love it when someone can change my mind about something, or get me to see things from a different perspective.

The reason that self-sovereign identity was a topic at a blockchain conference was because the whole idea of blockchains is decentralization, moving away from systems which are controlled by a central body. This gives “power to the people”, so to speak. “Satoshi Nakamoto” was the first to implement blockchain technology as a way for people to exchange currency without relying on banks. These topics are too large to go into detail about, but read up on the mysterious Nakamoto, bitcoin, blockchains, and Ethereum if you’re interested. It’s quite fascinating. Blockchains are databases, but they aren’t structured like traditional table-style databases. They’re blocks of transactions linked linearly like a chain that grows with each new block of transactions.  The chain gets downloaded to every computer that’s running the blockchain’s software, and each block has a link in it from the prior block, making this a very secure way to store and transfer data.

The chain gets downloaded to every computer that’s running the blockchain’s software, and each block has a link in it from the prior block, making this a very secure way to store and transfer data.

And making it a thought-provoking alternative to handing our identity data to every Joe Schmoe who asks us for it. As Antonopous asked, “What information do they need?” As in, really, what information does your bank need about you, and when? Do they need your home address in order to store your money “for” you (when, really, you’re loaning that money to them.) “It’s not identity that they need,” he said, “it’s secure attestation.”

If you’re like me, and you don’t care that data about yourself is being stored by the government, think about this. Imagine you’re eighteen and idealistic and you believe the current political party’s philosophies are wrong. You post these opinions on social media, and you join groups that rally in opposition to the government that you think is wrong. Twenty years later, you’re a mother of two, holding a stable job, political parties have changed over the years, swinging radically from one pole to the other until now there is a totalitarian government in place that is way worse than Trump. If you don’t think that’s possible, look at Argentinian history. In the years 1976 to 1983 an estimated 30,000 civilians disappeared due to the “ideological war” doctrine adapted by the government. This government’s belief was that the social base of insurgency needed to be eradicated, and they used precedent – incidents cited from aggressive attacks made by prior governments – to justify their way of squelching civil discord. This government was getting rid of citizens who they believed had anti-government points of view. This wasn’t that long ago. This was the EIGHTIES. Ferris Bueller was plotting ways to take a day off of school.

Still … it was Argentina, right? Far away. Nothing like that would happen in our backyard. But political boundaries become fuzzier as the world becomes more global. Big data is global. Blockchain is global. Machine learning is global.

Tying this back to 9/11 and the tech conference, Antonopoulos shared some intriguing thoughts about digitally remembering a person’s past. He postulated that one downside to the infinite memory retention of machine-driven databases is that a person’s lifelong data never goes away. Historically, we tend to forget certain things about people. If they regret a mistake they made, and they change, in time we take them at their current value, forgetting and forgiving that past mistake. This human experience will not be possible in a system in which data from “forever-back” is stored and pulled up when an authoritarian wants to assess our character for whatever reason. What happens to that human experience of making mistakes, regretting them, working to change, changing, and finding reward in our change for the better?

Very interesting.

Very interesting.

Joe Cutler thoughtfully questioned whether there are times when it is good to remember. For example, with 9/11. He said that he was in NYC and saw the words “Remember” hauntingly written around the areas of attack. Wasn’t it good to remember in cases like that? To try to reduce risk in the future?

Antonopoulos quickly interjected, “Remember what?” That hit my cerebrum. Remember what? He continued, “That the Saudis did it, and they are our best-funded ally?”

Hmmmm.

“We know who did it,” he said. “We know exactly who did it.”

I wondered what the people who had posted pics of veterans raising US flags and slogans of “We Remember” on social media were remembering. I wondered if you polled them and asked, “Who did it?” how many would know it was some Saudis.

So, this topic that I thought would be the least interesting of the talks in the conference became the most interesting to me. What would “forgiveness” look like in our big data future? Ana Badour proposed the possibility of allowing people to file for “identity data bankruptcy” to have mistakes that were atoned for “forgotten”. Is that possible?

Should it be?